What’s next for the New York Asian Film Festival!/Japan Cuts? Why, the latest from one of the funniest comedic filmmakers working in Japan today, and something called “The Atrocity Exhibition”?

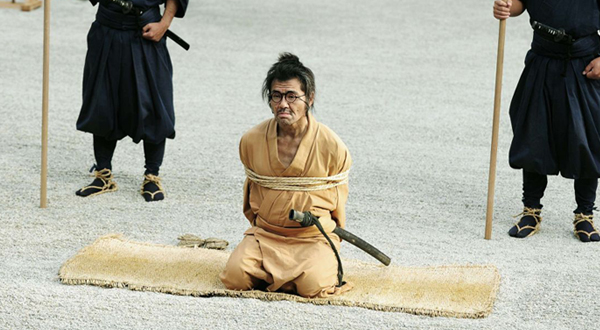

The Scabbard Samurai

Comedies are tricky in almost any instance, but when it comes to comedies from a foreign land, they’re an especially tough sell. Cuz, you know, stuff that’s funny here isn?t necessary so over there, and vice versa, due to cultural difference, blah, blah, blah. Thankfully, Hitoshi Matsumoto’s movies are a nice mishmash of deadpan and physical comedy, which is fairly universal. And this third film, aside from being the most grounded in reality (and isn’t another bio pic of a dude that grows very large to fend off giant monsters that attack Tokyo, aka Big Man Japan, or some other dude that’s stuck in a stark white room that has tiny penises sticking out of it, aka Symbol), it’s also about hard hard it can be to make someone laugh. Specifically a grief stricken child whose mom died from a horrible plague and hasn’t been able to crack a smile since. Enter Nomi, aka the Scabbard Samurai, who as the name implies, is a samurai without a sword, just the sheath. We see early on that he’s also a bit of a coward, but a resilient one; despite numerous assassination attempts from wacky bounty hunters, he kicks ticking. Though it’s his daughter who keeps him going, despite the fact that she’s also constantly reminding him of what a big coward her father is.

Turns out, dad is guilty of desertion and is apprehended by the authorities. To restore his honor, the local Lord suggests that he do the right thing and commit seppuku. Or, he can attempt the 30 Day Deed, in which he has a month to try and make the big boss’s son smile, who is the aforementioned sad little boy. The Scabbard Samurai gets one attempt each day, and if unsuccessful, Nomi really does have to commit ritualistic suicide. The challenge is accepted, much to the chagrin of his daughter. Not helping is how dad is not the least bit funny, because he too is deeply depressed, and this causes his daughter to repeatedly proclaim, with much annoyance and disgust, that dad should grow a pair and just kill himself already. But failed attempt after failed attempt prompts the two guards who have been assigned to keep an eye out on Nomi to get involved, and soon they begin workshopping their own ideas as to what’s funny, with Naomi being the guinea pig. At first, the ideas are fairly modest, like jumping through a flaming basket, but they progressively become more grandiose, like lifting a large pile of stones with his nose, and even semi-high concept, like having a one person sumo match. Basically, the movie becomes a Japanese variety program, set during Feudal times. Eventually the guards become super involved and super invested; they honestly want Nomi to win. Even his daughter has a change of heart and begins to recognize what kind of person her father is, as well as what he’s really trying to do.

At one point, the guards and Nomi’s daughter requests that the daily stunt be performed at the beach. This particular attempt fails like all the others, but because the public was able to look on, the Scabbard Samurai is a sudden hit and everyone is invited to witness each subsequent attempt from that point forward. And soon he becomes a local celeb that everyone is firmly rooting for, even the bounty hunters who had previously attempted to cash in on his reward. Much has been said about the movie, largely positive, and I wholeheartedly agree with the critic; Scabbard Samurai‘s core strength is its simplicity. The film effectively conveys a challenge that many of us have encountered first-hand, which is trying to cheer someone up, along with how comedy in general is murder. Also, deadlines kinda suck, don’t they? The story is told in a very straightforward manner, with zero need to rely on overly complicated, semi-pretentious subtext, or moral message that’s are super obvious, yet bashed into your head like a blunt object nonetheless. Which is also why, when the emotional gut punch is delivered, it actually works and doesn’t cause one’s eyes to roll. I went in expecting to really dig first first 99% of The Scabbard Samurai, but was fully prepared to hate the final 1%, and that definitely did not happen. True, the ending is pretty hooky, but I’d take that any day over the nonsense that was Symbol‘s finale. There’s one final screening, tomorrow afternoon/later today at 1pm, at Japan Society. A definite must see.

The Atrocity Exhibition

? aka three films that were advertised as “the most extreme, challenging, and jaw-dropping films we?re showing this summer”, according to the NYAFF’s description. So, were the good delivered as promised? Yes and no.

Let?s Make the Teacher Have a Miscarriage Club

The star of the night was, not surprisingly, the movie with the most intriguing and enticing title. There have been countless films, especially from Hollywood, that try their best to illustrate how heinous and deplorable teenage females can be. Those who, while on the road from little girl to womanhood, take a turn into pure evil for whatever reason. But absolutely none of those can touch Let?s Make the Teacher Have a Miscarriage Club, which is unquestionably the new gold standard for the genre. At the center of it all is the war between Ms. Sawako, who appears to be the only teacher in her junior high that gives a damn about her job (though in her coworkers? defense, it would seem that Japanese parents are even more stubborn and stupid than their American counterparts), and Mizuki, who leads a gaggle of easily led and just as morally reprehensible junior high girls (except she’s much, MUCH worse). When the leader of the clan learns that their beautiful and demure homeroom teacher is four months pregnant, the titular pact is formed. Because the idea of Sawako having sex, which obviously led to her becoming an expectant mother, is gross, and she therefore must be punished.

The methods employed are pretty aggressive early on, everything from slipping poison into their teacher’s lunch to rigging her chair so that she’s have a hard fall. What makes the movie is how Sawako tries her best to remain stoic, while also defending herself, which does not go over well with her bosses (who are at the absolute mercy of parents, no matter how ignorant they might be), and the spine-chilling performance of girl who played Mizuki, who clearly is not a professional actress, but her wooden delivery actually makes her character all the more frightening (she’s seriously the most evil thing ever to don Japanese school girl attire, ever). Many have compared it to Confessions, from the NYAFF two years ago, and I too dug the less elegant and much grittier take on the teacher vs student dynamic, which is mostly due to necessity, since it has a nothing budget (though I could have done without the at time amateurish camerawork). But is it superior? No, because the ending flat out sucks, in the way that way too many Japanese movies end up copping out: someone says something “profound” and then it just ends. An annoyance I touched upon to in my Smugglers review, but here it makes even less sense. What a crock.

The Big Gun

Movie number two, The Big Gun, was much like the one that preceded it: the title pretty much tells you everything you need to know. It’s about Ikuo, who owns and operates his own factory, one that has been shut down due to a serious lack of cash flow. Salvation comes in the form of a job, on the behalf of the yakuza: put his equipment to good use by making copies of revolvers for them. Which Ikuo and his brother does, and while they’re not perfect, they’re good enough for them make even more. And more after that.

Unfortunately, not only has the money yet to materialize after a good while, but it becomes abundantly clear that their new bosses will get exactly what he wants or else. Hence why Ikuo produces a little something on the side to fight back: the big gun. The movie, which is played fairly straight throughout, gets unintentionally comical at the end, due to the no budget special effects. Not only is revenge a dish served cold, but with an ample side of toy cars on fire. Though things sorta just end here, but given the one trick pony of the premise, I wasn’t nearly as offended as with the previous film.

Henge

And finally we have Henge, by the same director of The Big Gun, and it showed. The title is apparently the Japanese term for metamorphosis, and is essentially a modern Japanese retelling of the Franz Kafka classic, with a dose of Tetsuo The Iron Man mixed in. Keiko is the frightened, but ultimately loyal wife of Yoshiaki, who has violent, full-body seizures and strokes on an almost daily basis. No real cause can be traced, though while under hypnosis, he does spout some bizarre, almost alien-like language. Eventually, Yoshiaki’s body begins to slowly take on a bizarre, insect-like appearance when entering his trance, until it fully envelops him. Naturally, people want to take him to the hospital, to cut him up into little pieces. But Keiko not only stands by her husband, but also has no problem with his grotesque appearance, which soon becomes the norm. In fact, she kinda digs it, and even has sex with him while in his gigantic bug/alien looking form. Yoshiaki also develops a craving for human flesh, so it’s a good thing he has a wife that’s willing to go around town at night, picking up up random dudes, so she can take them home and serve her husband a fresh meal. If only all guys were as lucky. Unfortunately, the cops eventually catch on, and the two become fugitives.

The inevitable confrontation ensues, and this is where the similarities to The Big Gun kicks in. Up until this point, it was mostly a drama that was less about a guy turning into some otherworldly creature, and more about the woman that’s caught in the middle. Though more importantly, the total lack of budget is something that was not noticeable, but it rears its head when everything all of a sudden becomes a kaiju flick,. Not only is Yoshiaki’s transformation complete, but he turns super huge, and turns into a rampaging monster, a la Godzilla, and the tall buildings look just as cheesy. The so bad it’s still not very good special effects are saved by a few, genuinely new to the table flourishes, like when Yoshiaki grabs an office building, and then shakes all its inhabitants out, who all plops onto the concrete blow in bloody fashion. Never seen Godzilla or Gamera do that. Anyhow, Henge was pretty neat, for what it was and then became. Catch if you can; no word on a home video release, but apparently it’s been a darling at every film festival its played at (some are even calling it the next big thing in J-horror), so there might be a chance that you’ll have a chance to see it eventually.

Pingback: Japan Cuts 2012: “Rent-A-Cat” & “Space Battleship Yamato” + Not A Broken Record, But A Severely Bent One | FORT90.com

Pingback: NYAFF 2014: “R100″ & “Moebius” & “Mr Vampire/Rigor Mortis” | FORT90